KATHLEEN K. HO and TIMOTHY S. O'DONNELL v. WINCHESTER BOAT CLUB.

KATHLEEN K. HO and TIMOTHY S. O'DONNELL v. WINCHESTER BOAT CLUB.

MISC 16-000688

July 25, 2017

Middlesex, ss.

FOSTER, J.

KATHLEEN K. HO and TIMOTHY S. O'DONNELL v. WINCHESTER BOAT CLUB.

KATHLEEN K. HO and TIMOTHY S. O'DONNELL v. WINCHESTER BOAT CLUB.

FOSTER, J.

Introduction

This is a dispute regarding an easement right to enter and pass over certain property owned by the Winchester Boat Club (WBC) by foot for the purposes of accessing Mystic Lake, to store canoes or small boats in the right of way, and to construct, install, and use a dock in the Mystic Lake along the right of way. On November 14, 2016, plaintiffs Kathleen K. Ho and Timothy S. O'Donnell (Plaintiffs) brought a Verified Complaint against defendant WBC regarding their rights to use a 12 foot wide easement to cross over WBC's property and access Mystic Lake. On February 21, 2017, the Plaintiffs filed an Amended Verified Complaint (Compl.). The Amended Verified Complaint seeks (1) injunctive relief, (2) title by adverse possession of the disputed property, and (3) a declaratory judgment pursuant to G.L. c. 231A as to Plaintiffs' easement rights. The same day, WBC filed its Answer to Amended Complaint and Counterclaim (Ans.).

On July 3, 2017, Plaintiffs filed a Motion to Enjoin Interference with Easement Rights (Motion for Preliminary Injunction or Mot.) and the Affidavit of Kathleen K. Ho (Ho Aff.). On July 18, 2017, WBC filed a Memorandum of Law in Opposition to the Plaintiffs' Motion to Enjoin Interference with Easement Rights (Opp.), Affidavit of Steph E. Hood (Hood Aff.), and Affidavit of Lawrence M. Beals (Beals Aff.). A hearing on the Motion for Preliminary Injunction was held on July 20, 2017, and the motion was taken under advisement. For reasons set forth more fully in this memorandum and order, the Motion for Preliminary Injunction is allowed in part and denied in part.

Discussion

A preliminary injunction may issue only if the moving party demonstrates (a) a likelihood of success on the merits, (b) that they face a substantial risk of irreparable harm if the injunction is not issued, and (c) that this risk of irreparable harm outweighs any risk of irreparable harm which granting the injunction would create for the nonmoving party. GTE Prods. Corp. v. Stewart, 414 Mass. 721 , 722-723 (1993); Packaging Indus. Group, Inc. v. Cheney, 380 Mass. 609 , 617 (1980). Thus, a showing of a high chance of success on the merits does not by itself constitute sufficient grounds to grant a preliminary injunction. The court must evaluate the combination of the moving party's claim of injury, chance of success on the merits, and balance the risk of irreparable harm to the moving party and the opposing party if the injunction is denied or granted. Ashford v. Massachusetts Bay Transp. Auth., 421 Mass. 563 , 564 (1995). "Only where the balance between these risks cuts in favor of the moving party may a preliminary injunction properly issue." Packaging Indus. Group, Inc., 380 Mass. at 617.

The following facts appear in the record and are credited by the court for the purposes of consideration of this request for preliminary injunctive relief. The Plaintiffs are the owners of property at 48 Everett Avenue in Winchester by deed from Phillip A. McIntyre and Nina Primm McIntyre (McIntyres) dated May 30, 2014, and recorded in the Middlesex South Registry of Deeds (registry) in Book 63682, Page 437 (Ho/O'Donnell Property). Compl. ¶¶ 1-2, 13; Ho Aff. ¶ 4, Exh. 2. WBC operates a seasonal boat club at 65 Cambridge Street, where its clubhouse is located, on the upper Mystic Lake in Winchester (WBC Property). Compl. ¶ 3. In 1990, WBC purchased a vacant parcel abutting the WBC Property, referred to as 65 Rear Cambridge Street (Lot A). Compl. ¶ 4; Ans. ¶ 4. In 1992, WBC acquired title to another vacant parcel, Lot B, abutting Lot A to the west and the Ho/O'Donnell Property to the east. Compl. ¶ 7; Ans. ¶ 7. In or around 1992 or 1993, the McIntyres constructed a stone wall along the rear property line that separated their backyard from Lot B. The stone wall included an opening that the McIntyres used to walk across Lot B to access Mystic Lake. Compl. ¶ 14; Ans. ¶ 14.

Mr. McIntyre told the Plaintiffs that in the early 1990s, WBC was replacing a dock and asked if he wanted to take the old dock. He stated that he took the dock and pulled it to the shoreline of Lot B and installed it in the area where the McIntyres had been accessing the lake on Lot B from their property. Mr. McIntyre said that the dock would sometimes become unfasted and he would drag it back to the shore and reattach it so the original location may have changed. Compl. ¶¶ 17-19; Mot. ¶ 4; Ho Aff. ¶¶ 12, 14, Exhs. 3-4. The dock is more than three feet wide. Mot. ¶ 5. The McIntyres have referred to the dock as "our dock." Ho Aff. ¶ 3, Exh. 1.

On July 15, 1996, the McIntyres entered into an agreement with WBC whereby the McIntyres deeded a portion of their lot, equal to 1,628 square feet, to WBC in exchange for a right of way to access Mystic Lake over Lot B (Agreement). The Agreement set forth the terms of the easement, which stated in part:

(a) The right and easement, in common with others nor or hereafter entitled, to use the strip of land (the "Right of Way") is twelve (12) feet wide shown as "12' Right of Way" crossing Lot 2 on a plan (the "Plan") entitled "Plan of Land in Winchester Mass. (Middlesex County)" dated April 9, 1994 and prepared by James Richard Kennan, P.L.S., recorded herewith, for passage by foot between land now owned by Grantee adjacent to the northerly boundary of Lot 2 and shown as Lot 3 on said Plan ("Lot 3"), and Mystic Lake, all as shown on said Plan and the right and easement to store a canoe or small boat on the Right of Way; and

(b) The right and easement to construct, install, attach and secure a dock and/or float no more than three (3) feet in width, along the southern boundary line of the Right of Way into said Mystic Lake.

(Easement) Mot. ¶ 2; Compl. ¶ 13, Exhs. H, I. The Easement further stated that the rights and easements set forth in (a) shall run with and benefit "Lot 3", the now Ho/O'Donnell Property, but that the rights and easements set forth in (b) shall run with Lot 3

only to the extent that such rights and easements have been exercised during the period that the Grantee named herein is the owner of Lot 3. Any successor to such Grantee as owner of Lot 3 shall have the rights and easements set forth in Subsection (b) above only to the extent that such rights and easements were exercised by the Grantee named herein, except that such successor owner shall have the right to repair any docks and/or floats that were installed by the Grantee named herein.

The Easement, along with the plan referenced therein (Kennan Plan) was recorded in the registry on March 18, 1998, in Book 28324, Page 61. Compl., Exh. I.

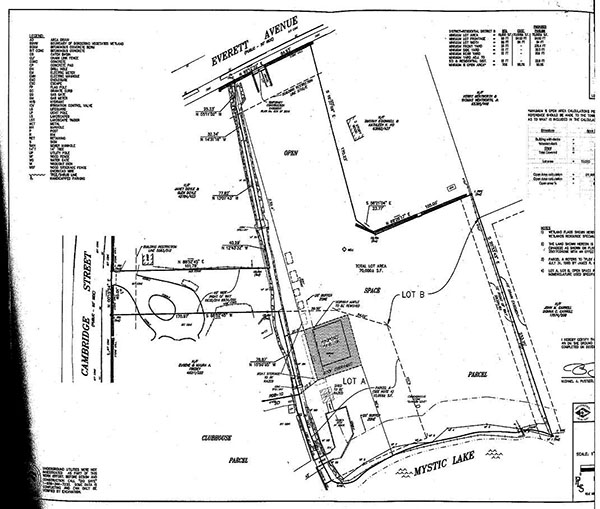

When the Plaintiffs were deeded their property from the McIntyres in 2014 it included the Easement granted to the McIntyres by WBC. Mot. ¶ 1; Ho Aff., Exh. 2. When the Plaintiffs purchased the Ho/O'Donnell Property, their right of way pursuant to the Easement was completely overgrown with trees and brush and was impassable. A chain link fence had been installed inside the eastern boundary of the right of way, reducing the width of the Easement from 12 feet to approximately 8 feet along the entire length of the right of way. It was also blocked at the shoreline by a section of a wooden picket fence, used to keep geese out of the Easement area and off WBC's property (goose fence), which ran along the shore of the lake and intersected with the chain link fence and across the right of way. Ho Aff. ¶ 6; Beals Aff. ¶¶ 10, 12. A second section of the goose fence was attached to the first with a hinge so that the fence could be moved so it did not completely block access to the shoreline or dock. Ho Aff. ¶ 17; Beals Aff. ¶ 12. Since the Easement was blocked, the Plaintiffs walked through the opening in the stone wall at the rear of their property and across Lot 4, as the McIntyres had done previously, to access the dock. The Plaintiffs used the dock freely to fish or sit on chairs enjoying the view. WBC did not object to the Plaintiffs use of the dock. Ho Aff. ¶ 7. A plot plan revised December 5, 2016 showing the relative location of the properties, the Easement, the dock, the chain link fence, and the goose fence is attached here as Exhibit A.

In July 2014, the Plaintiffs became members of WBC and they continued to use the dock for the rest of 2014, 2015, and into mid-2016. Throughout this period, WBC never raised any objection to the Plaintiffs' use of the dock, nor did it communicate any claims of ownership to the dock or club rules about the use of the dock. Mot. ¶ 9; Ho Aff. ¶ 8. On May 18, 2016, WBC sent a letter to the Plaintiffs claiming ownership to the dock and stating that "any use of the WBC dock by you is at your own risk." Mot. ¶ 10; Ho Aff. ¶ 15. In the spring of 2016, WBC had the area of the Easement staked, marking the property with stakes and ties. The stakes at the shoreline indicated that the beginning of the 12 foot Easement was on the other side of the chain link fence and that the dock was not located within the Easement area. Mot. ¶ 11; Ho Aff. ¶¶ 16, 21, Exh. 4. In July 2016, WBC suspended the Plaintiffs' membership. Because the Easement was impassable and blocked by the goose fence at the shoreline, the Plaintiffs stopped using the dock around this time. Mot. ¶ 12; Ho Aff. ¶ 18.

In August 2016, the Plaintiffs obtained permission from the Conservation Commission to clear out the Easement in order to make it passable, but WBC had already removed a great deal of the overgrowth in the right of way. Ho Aff. ¶ 19. In October 2016, WBC removed the first section of the goose fence that blocked the right of way, and propped it up against the chain link fence. Ho Aff. ¶ 22, Exh. 5. In November 2016, WBC removed all of the chain link fence except the portion nearest Mystic Lake. They also moved the first section of the goose fence that was propped against the chain link fence, and propped it at an angle along the remaining section of the picket fence. Mot. ¶ 13; Ho Aff. ¶ 23, Exh. 5; Beals Aff. ¶ 10. In May or June 2017, WBC moved and installed sections of the goose fence such that they again block the Plaintiffs' access to the shoreline from the Easement area. Mot. ¶ 15; Ho Aff. ¶ 24, Exh. 6.

The Plaintiffs now seek an injunction to enjoin WBC from inhibiting, obstructing, or otherwise impeding the Plaintiffs and their assigns from accessing the lake through their claimed Easement across Lot B.

LIKELIHOOD OF SUCCESS ON THE MERITS

In order for a preliminary injunction to issue, the moving party must demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits. Robinson v. Secretary of Admin., 12 Mass. App. Ct. 441 , 451 (1981). Based on the factual allegations, the Plaintiffs have demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits of their claim to easement rights over WBC's property to access the lake and to store their canoes and small boats in the right of way. "An easement is an interest in land which grants to one person the right to use or enjoy land owned by another." Commercial Wharf E. Condominium Ass'n v. Waterfront Parking Corp., 407 Mass. 123 , 133 (1990). It "is by definition a limited, nonpossessory interest in realty," and, as such, "is created to serve a particular objective." M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 92 (2004). The extent of any easement is fixed by the terms of the conveyance creating the easement. Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998), citing Restatement of Property §§ 482, 483(d) (1944).

The deed from the McIntyres gave the Plaintiffs all the rights under the Easement. There is no dispute that the Plaintiffs are entitled to enjoy a right of way over Lot B. The language of the Easement is unambiguous and clearly runs with and benefits all present and future owners of the Ho/O'Donnell Property. Although the Easement states that it is to be a 12 foot right of way, this does not mean that the Plaintiffs are entitled to the full width of the Easement. The owner of the burdened property can make reasonable changes in the location and dimensions of an easement, "but only if the changes do not (a) significantly lessen the utility of the easement, (b) increase the burdens on the owner of the easement in its use and enjoyment, or (c) frustrated the purpose for which the easement was created." M.P.M. Builders, LLC, 442 Mass. at 91, citing Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) § 4.8(3). This applies to circumstances "where there has been no relocation of the easement, but where the width of the unobstructed easement has been narrowed in some places, while still leaving travel . . . unimpeded." Martin v. Simmons Properties, LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 12 (2014).

The chain link fence does not lessen the utility of the Easement, increase the burden on the Plaintiffs in its use and enjoyment, or frustrate the purpose for which the Easement was createdto access the lake or to store canoes and small boats. The portion of the chain link fence closest to the lake that was not removed by WBC narrows the physically available portion of the right of way from 12 feet to 8 feet. This is available area is wide enough for the Plaintiffs to get to the lake on foot and to bring and store their canoes or small boats. The terms of the Easement do not require the right of way to remain open for its full width. Further, it is not clear that WBC installed the chain link fence. Evidence suggests that the chain link fence was in existence when WBC granted the Easement to the McIntyres by the Agreement in 1996, it was there when WBC acquired Lot B in 1992, and may have been there as far back as 1979. Hood Aff. ¶ 4. Based on this, the removal of the fence is not likely conduct for which WBC is responsible and not the proper subject of an injunction against WBC. See Martin, 467 Mass. at 21 ("Because Martin was unable to establish that Simmons placed the fill . . . Simmons has no obligation to remove the fill.").

This, however, is not the case for the goose fence. The goose fence, installed parallel to the shoreline at the end of the right of way closest to the lake, is blocking the Plaintiffs' access to the lake. It makes no difference that the configuration of the goose fence has been changed several times recently, with loose parts being removed, set aside or rearranged, or that it is not affixed in a particular location. Nor does it matter that the goose fence was not intended to obstruct passage to the lake by the Plaintiffs over their right of way, but instead for the purported benefit of protecting WBC's property and the Plaintiffs' property from goose intrusions. The location of the goose fence does in fact lessen the utility of the Easement by blocking several feet of the already narrowed 8 foot right of way and imposes an additional burden on the Plaintiffs by requiring them to move the goose fence each time they desire to access the lake by foot or transport their canoes and boats to and from the water. This is an unreasonable interference with the Plaintiffs' Easement rights. The Plaintiffs have demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits of their easement claim as to the goose fence.

The Plaintiffs have failed to demonstrate such a likelihood of success with respect to the dock. The Plaintiffs allege, based primarily on inadmissible hearsay statements, that they own the dock through the McIntyres. The hearsay statements consist of a printed list of questions and answers that the McIntyres provided when the Plaintiffs were considering whether to submit an offer to purchase their property, a phone conversation between Mrs. Ho and Mr. McIntyre in May, 2016, and an email from Mr. McIntyre to Mrs. Ho in May, 2016. Ho Aff. ¶¶ 2, 12-13, Exhs. 1, 3. In these statements, Mr. McIntyre contends that WBC gave him the dock in the early 1990s when it was renovating its main dock and he installed it along the shoreline in the area of the Easement, where he continued to use and treat the dock as his own. Ho Aff., Exhs. 1, 3. Even if these hearsay statements were admissible, WBC presents enough conflicting evidence that the Plaintiffs cannot at this time demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits of their claim to the dock.

WBC states that the McIntyres never acquired ownership of the dock when it was moved from the area near the clubhouse to Lot B. Beals Aff. ¶¶ 7-8. Rather, the McIntyres used the dock with permission of WBC, along with other members, since they were members of WBC. The dock came to be known as the canoe and kayak dock and club members use it to launch canoes and kayaks into the lake. Hood Aff. ¶ 2; Beals Aff. ¶ 8. Beginning in 2009, WBC annually registered the dock, along with all of its other docks, with the Winchester Board of Selectmen. Beals Aff. ¶¶ 4-6, Exh. A. Mr. McIntyre acknowledges in his May, 2016 email that neither the dock nor any other legal interest in it was conveyed by deed or otherwise formally given to him, and that he did not have marketable title to the dock. Ho Aff., Exh. 3. Likewise, Stephen Hood, WBC's manager from 1979 to 2012, recalls no transfer of ownership of the dock to anyone. Hood Aff. ¶ 3.

The McIntyres' lack of ownership in the dock is also supported by the terms of the Agreement and subsequently executed Easement, following Mr. McIntyre's supposed acquisition of the dock. The Easement provides the current owner with the right "to construct, install, attach and secure a dock." If the McIntyres had already been given the dock by WBC in the early 1990s, as the Plaintiffs maintain, then WBC's granting them in the Easement the right to construct and install a dock of their own would be futile since they would have no need for a right to build another dock. That the dock is the one that the Easement granted the McIntyres the right to build is called into question by the fact that the dock is more than six feet wide, wider than the maximum allowed width of three feet under the Easement. This right to construct a dock was only given to the McIntyres and was not transferrable to subsequent property owners unless the McIntyres constructed the dock themselves. There is evidence that the McIntyres never exercised their right to do so and that right expired as of 2014 with the conveyance of the property to the Plaintiffs. The fact that the Plaintiffs used the dock after they took title to their property would also not confer ownership since it would have been with permission of WBC, which they were members of at the time. Because of these conflicting facts presented by WBC and the lack of admissible evidence provided by the Plaintiffs, they have not at this time demonstrated a likelihood of success as to their ownership of and rights to use the dock under the Easement.

BALANCE OF HARMS

When seeking a preliminary injunction, the moving party must show that an irreparable injury would occur without immediate injunctive relief. LeClair v. Town of Norwell, 430 Mass. 328 , 331 (1999). To show "irreparable harm," the moving party must show that, without the injunctive relief, it may suffer a loss of rights that cannot be vindicated should it prevail after a full hearing on the merits. American Grain Prods. Processing Inst. v. Dep't of Pub. Health, 392 Mass. 309 , 327 (1984). Harm to the moving party is not irreparable if it can be offset by a final judgment, rendered either at law or in equity. Packaging Indus. Group, Inc., 380 Mass. at 617 n.11. In addition, there is no irreparable harm sufficient to support the granting of a preliminary injunction if the asserted harm is speculative. Commonwealth v. County of Suffolk, 383 Mass. 286 , 289 (1981). When analyzing the potential risk of irreparable harm, the court must balance the risk of harm to the moving party against any similar risk of irreparable harm to the opposing party. Packaging Indus. Group, Inc., 380 Mass at 617. "What matters as to each party is not the raw amount of irreparable harm the party might conceivably suffer, but rather the risk of such harm in light of the party's chance of success on the merits. Only where the balance between these risks cuts in favor of the moving party may a preliminary injunction properly issue." Id.

Because the Plaintiffs have only demonstrated a likelihood of success on their claim with regard to the goose fence impeding their Easement rights, the balance of harms need only be addressed with respect to this issue. The Plaintiffs desire to use the right of way to access the lake by foot and to transport or store their canoes and small boats, particularly during the summer months. WBC does not dispute that the Plaintiffs retain the right to access the lake across the deeded right of way, swim in it, launch canoes, fish, and otherwise make full use of it. The present location of the goose fence blocks a portion of the right of way, making it difficult to pass through without moving the fence out of the way, especially if attempting to transport a canoe or boat to and from the water. This harm is not speculative. The location of the goose fence has and is currently preventing the Plaintiffs from fully using their rights granted under the Easement.

The potential for irreparable harm to the Plaintiffs outweighs any harm to WBC in removing the goose fence from the Easement area. Though WBC claims that the goose fence is for protection against the filth generated by goose droppings with the Easement area and WBC's property, the effectiveness of the fence in actually doing so is questionable considering it doesn't block off the entire property from the water and there are several gaps in the fence where geese can enter. Opp. at 2; Ho Aff., Exhs. 4-5. As noted by WBC, the goose fence is lightweight, not affixed, and easily movable. Opp. at 2. It will require little time and effort for WBC to remove the goose fence, whereas keeping the fence in its current location would continue to impede the Plaintiffs' reasonable use and enjoyment of the right of way. "An interference with an easement holder's use of the land amounts to an infringement of a valuable property interest." Texon, Inc. v. Holyoke Mach. Co., 8 Mass. App. Ct. 363 , 366 (1979). "It is well settled in this Commonwealth that real property is unique and that money damages will often be inadequate to redress a deprivation of an interest in land." Greenfield County Estates Tenants Assoc., Inc. v. Deep, 423 Mass. 81 , 88 (1996). When balanced against the impact to the Plaintiffs in keeping the goose fence in its current location, and in light of the Plaintiffs likelihood of success on the merits of their Easement claim, the minimal effort in removing the goose fence and losing whatever negligible protection the fence currently provides does not outweigh the harm.

CONCLUSION

For the above mentioned reasons, the Motion for Preliminary Injunction is ALLOWED IN PART and DENIED IN PART. The Winchester Boat Club is ENJOINED from inhibiting, obstructing, or otherwise impeding the Plaintiffs and their assigns access to the Easement area and is ORDERED to remove all sections of the goose fence that are located within the right of way.

The findings and rulings contained herein are necessarily preliminary in nature. Thus, these findings and rulings are neither intended, not should they be construed, as having any precedential weight or effect in further proceedings in this case, all of which shall be determined in the light of the evidence offered and admitted on those occasions. Should further-developed evidence or circumstances warrant, any party may move for the modification or dissolution of this order at any time.

SO ORDERED.

exhibit A